Should instructional coaches tell teachers what to do?

Spoiler alert: the answer is "almost never."

(photo from Sports Illustrated)

Today I encountered an article that goes against pretty much all the ways I coach teachers. I’m glad I read it. It has led me to think about what I do, why I do it, and why it works.

Rick Hess quotes Michael Sonbert in the article. A little Googling of Michael Sonbert reveals an unnecessarily macho book cover and a website touting his ability to get teams to work together well. That’s fair enough: I’m in favor of really good teams. If I dug a little, I might find some useful tips within. So when he says that Jim Knight, who has forgotten more about instructional coaching than the rest of us will ever know, is not doing it right, well, I perk up my ears.

In Sonbert, my perked-up ears have picked up discordant, cacophonous sounds.

Still, I take a lot of pride in understanding people who disagree with me, and in conceding points where I am wrong. So let’s start with where Sonbert is right before going on to the many, many places that he is mistaken.

His thesis is this:

Schools need to have an agreed-upon vision for instructional excellence. Once that vision is clear (by the way, teachers can absolutely contribute to that vision), coaches don’t need to play guessing games with teachers but can instead compare what’s happening in the teacher’s classroom against the exemplar and then tell (yes, tell) the teacher, with compassion and kindness, precisely what needs to get better and what the teacher should do to get there.The coach should then model the skill the teacher needs to improve upon and have them practice that skill multiple times, giving feedback throughout, until they begin to build automaticity.

So…where is he right?

He’s right when the teacher is new or really struggling.

Knight’s partnership approach, which Sonbert disdains, is admittedly not effective if a teacher is too green or overwhelmed to bring anything to the partnership. Someone who is hopelessly lost is not going to do a good job at becoming found. Giving that teacher a few things to try is a good idea. Now, Sonbert wants the coach to be the expert to tell (and man, that snide parenthetical of “yes, tell” is sure telling, isn’t it?) pretty much every teacher what to do. This is a good idea in situations where the coach has way more expertise than a teacher. When that’s the case, and when the situation in the classroom is dire, a coach can say “Hey, here are a few things you can try.” Why a few things rather than Sonbert’s single, unnamed thing? Because no one–least of all adults–wants to lose their autonomy. Even if my boss is right, I do not respond well to being told what to do. Neither do you. Neither does Sonbert. So even the most struggling teacher should be given a few really good options for how to proceed, so that they own the choice and the results. But he is right that it’s not best practice to wait for a teacher in a deep, dark place to develop ideas. A directive approach is needed there.

I appreciate Sonbert’s urgency to make a classroom better, and I share his desire for our results to be measured in student learning rather than in teachers feeling good.

But he is off the mark in so many ways. So many.

The first is what I see as simplifying what a teacher does, perhaps even to the point of contempt. Take this paragraph:

Knight’s approach assumes that getting a teacher to a place of being highly effective is like trying to answer a confusing, ambiguous riddle. But it’s not. I’ve worked in hundreds of schools in the past 15 years. The trends in classrooms across the U.S. are staggeringly similar, and what to do about them is surprisingly straightforward.

Let’s tackle the second part of that first. He is saying that the answer to getting all teachers to teach and all students to learn is straightforward.

Wait…what?

Has Sonbert ever been in a classroom? A classroom is a place with as many as 30-plus different souls with different needs and different tastes and different backgrounds all put together in front of one teacher (with their own needs and tastes and backgrounds) in a neighborhood that has its own character and peccadilloes, as well as state and local standards that each kid needs to reach? Kid A is annoyed because they just got dumped by a girlfriend, kid B didn’t eat breakfast, kid C is absent because of a chronic illness, kids D and E are bored by the subject, kid F finds school irrelevant, kid G is thrilled and wants to go way above and beyond what the others can do, and the teacher is all out of coffee. Sometimes the teacher is provided appropriate tools for the task at hand, and sometimes not.

Sonbert, if I have him pegged correctly, would call all of this teacher whining or pre-emptive excuse making. It isn’t that. He is right that we need to get all kids from A to beyond Z to learn in this room, and that it is the job of both coach and teacher to make that happen.

But what exactly is the “surprisingly straightforward solution” that will make this happen? Sonbert doesn’t tell us what it is, and it’s because such a single and straightforward solution does not exist. If it did, we’d all be doing it by now. A classroom is a complex, interdependent environment that requires complex and multiple solutions to meet all of those mixed-up needs. I always blanch at people who suggest there are simple and single solutions to complex and nuanced problems (like gun violence, or US health care, or the Seattle Mariners winning the AL West). There are not, and somebody who says “all you need is this one thing” always trips my suspicions.

The other half of Sonbert’s quote is problematic for different reasons. He characterizes a teacher and a coach thinking together about the next move a teacher should make as two people “trying to answer a confusing, ambiguous riddle.” Of course, since Sonbert believes he has the surprisingly straightforward answer to all of education in his brain (and won’t tell us what it is), he views this as a waste of time and effort.

This isn’t how I experience these conversations, nor (if I may speak for them) the teachers I work with. The coaching cycle, as I enact it, goes something like this:

1. Establish reality. Make sure the teacher sees their classroom as it is. Ideally, this is with data around either engagement or achievement.

2. Determine what the teacher wants to get better at. 90% of the time, this is the thing that will be best for student learning. In spite of what Sonbert believes, teachers have a better sense of what their students need than a coach who is just in there for a period or two.

3. Brainstorm with the teacher the best ways to make that happen. Here, the coach provides a few possible techniques to use to attain the goal, and the teacher chooses one.

4. Try the technique out in class (sometimes it is the coach who does this, sometimes the teacher).

5. Take data again. If it shows that that teacher has reached their goal, celebrate and move on. If it does not, go back to step 2.

I don’t see anything in here about a “confusing, ambiguous riddle,” except insofar as a classroom of students is messy and complicated and there are multiple ways to approach such a place. But what I do see is a process superior to the one Sonbert suggests, which is this:

1. Tell the teacher what to do.

2. Model it until the teacher gets it.

3. Leave.

And this leads us to the third way that Sonbert is off-base, which is his failure to see teachers as human beings who respond as well to losing their autonomy as any of us do, which is to say not at all.

I’ve been the teacher who has been told what to do. Sometimes I have rebelled. Sometimes I have half-assed. Never have I enthusiastically capitulated.

Teachers are professionals. Sonbert treats them like machines that need to be kicked if they glitch. Why would you hire a teacher with an advanced degree and possibly tons of experience and ignore their take on their own classroom? Sonbert eventually says that partnership can happen “when teachers are expert planners and have incredible classroom culture,” but in viewing such teachers as the exception, he underestimates most of the wonderful humans I work with. They know their stuff, and to ignore all that in favor of simply following Sonbert’s orders is offensive, and therefore would be ineffective.

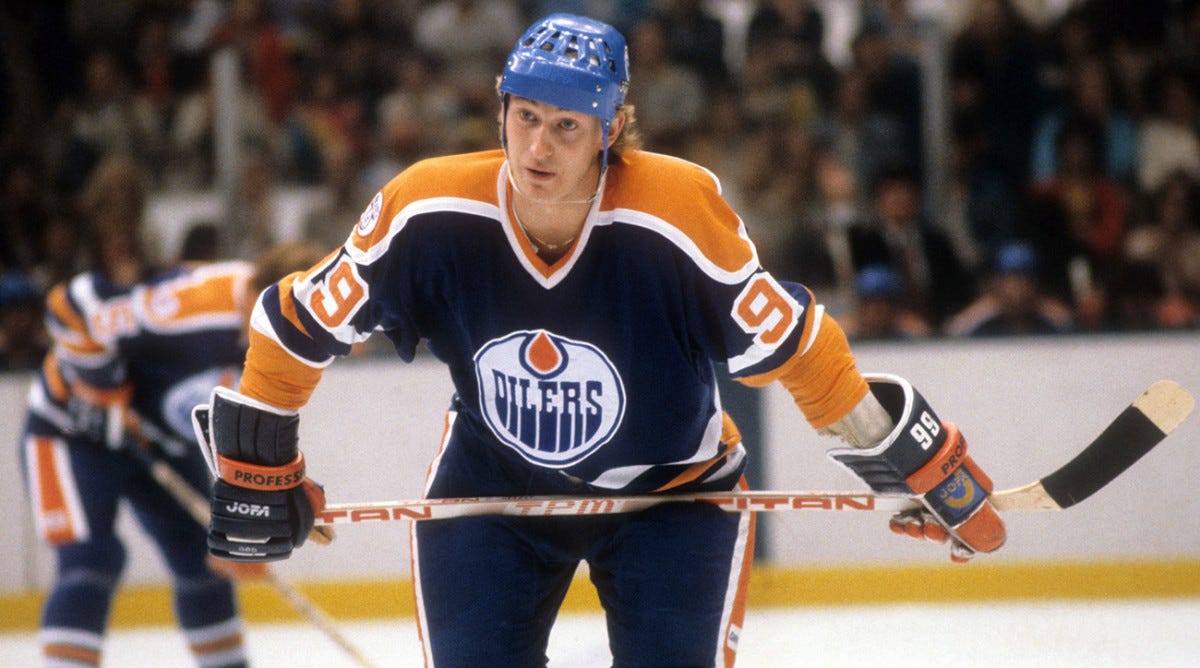

Sonbert also assumes that being a good teacher automatically makes someone a good coach. He says that we should not pass up on an opportunity to have Serena Williams teach us about tennis. But she might be a terrible coach. In fact, we can find far more examples of great athletes who were terrible coaches than great athletes who above-average coaches. Just off the top of my head, I can list Ted Williams, Maury Wills, Wayne Gretzky, Magic Johnson, Isiah Thomas, Wilt Chamberlain, and Bart Starr as people who were among the best in the world at playing their sports who were absolutely lamentable as coaches. I suspect that it was because they didn’t understand what made them so good on the field, and therefore didn’t know how to make people better.

As I am writing these words, the Texas Rangers are about to win the World Series. Their manager, Bruce Bochy, has solidified his spot in the Hall of Fame with this victory.

(photo from For The Win)

And guess what? He wasn’t much of a player on the field.

(photo from Baseball Reference)

What makes him successful as a manager was not ordering people around or modeling. It was figuring out what each person on the team brings to the table and working with them to create the best possible version of themselves. That’s what coaching is. Not saying “do this,” as Sonbert suggests. Instead, it’s taking after Bochy. It’s figuring out your team’s unique talents and personalities and maximizing them.

I was a good classroom teacher, but I am finding that my teaching abilities are about 8th on the list of what is valuable as an instructional coach. For instance, today I spent a wonderful half hour coaching a teacher who wanted her German 4 students to gain more confidence in their own ability and fluency. I don’t speak or read German. I don’t know much about how to teach World Languages. Does Sonbert think I should make a demand of this teacher to do a specific technique, get in front of her students and try it, and only leave when she has mastered that technique? (I am assuming that Sonbert’s surprisingly straightforward technique would be effective here, if he cared to share it.)

No. Instead, I listened closely to the teacher, explored her students’ current reality, asked a couple of questions, and as a result of this exploration of her problem of practice (a process Sonbert would ridicule as a waste of time), the teacher now has a new idea she’s ready to try. We’ll see if it works by measuring the kids’ self-reported sense of confidence in the language. If it fails, we’ll try the next thing. The teacher is empowered and excited because her knowledge and expertise were essential to the partnership. Had Sonbert been coaching her instead, her ideas and expertise would have been ignored. Because of this, I guarantee you ideas would not have been implemented. His coaching would have failed both teacher and students.

On top of that, I have found modeling to be a useful but somewhat overblown part of the coaching cycle. It’s useful for some specific routines. I’ll be modeling a Silent Seminar tomorrow for a teacher who wants to get her comatose first period to do some interacting. If that teacher wanted to conduct the lesson herself, that would be fine too, since she’d still be working towards her goal of more engagement from a silent, sleepy crew. It doesn’t much matter whether she learns it by being taught and then trying it or if she learns it by watching me do it. The point (as Sonbert would agree) that students are more engaged with the material, and I am confident we’ll be able to accomplish that quickly—possibly within a week of the teacher coming to me for coaching.

Sometimes, a coach modeling can be deleterious, like when a teacher is struggling with classroom management. If I take over a struggling teacher’s class and succeed, that actually undermines the teacher even more. Also, my management style (as a 6’3” guy with a sarcastic streak) won’t be right for someone else, like the wonderful student teacher I had (a 5’5” woman who kids saw as sweet and maternal). Ordering that she do it one way would have been ridiculous because what is best for one teacher is not best for everyone. Sonbert’s dictatorial approach doesn’t allow for individual differences. Everyone has to do it his way.

In the end, Sonbert thinks that most teachers are so devoid of professional value that they simply need to simply be given orders to follow. Rather than being consulted for their professional knowledge, they need to be told (yes, told) what to do. Perhaps you’ve had a boss who suffocated you like Sonbert would, who found your contributions unimportant and your creativity irrelevant. How long did you stay at that job?

Teachers and principals, how much autonomy do you feel teachers should have? How much exploration should a coach and teacher engage in—or are students better off if the coach-teacher relationship is directive?